Who Is Joseph Ratzinger–– Pope Benedict XVI

Biography of Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI)

1927

Ratzinger is born on April 16, Holy Saturday in Marktl am Inn, and is baptized the same day. Reflecting on this experience in his memoirs, he says:

To be the first person baptized with the new water was seen as a significant act of Providence. I have always been filled with thanksgiving for having had my life immersed in this way in the Easter Mystery . . . the more I reflect on it, the more this seems fitting for the nature of our human life: we are still waiting for Easter; we are not yet standing in the full light but walking toward it full of trust. [p. 8, Milestones]

Ratzinger admits it is not easy to say what his ‘hometown’ is. As a rural policeman, his father was transferred frequently, and his family was continually on the road.

1929

Ratzinger’s family moves to Tittmoning, a small town on the Salzach River, on the Austrian border.

1932

December: Due to his father’s outspoken criticism of the Nazis, Ratzinger’s family is forced to relocate to Auschau am Inn, at the foot of the Alps.

1937

Ratzinger’s father retires and his family moves to Hufschlag, outside the city of Traunstein, where Josef would spend most of his years as a teenager. Here he begins classes at the local gymnasium for classical languages, where he studies Latin and Greek.

1939

Ratzinger enters the minor seminary in Traunstein, the initial step of his ecclesiastical career.

1943

Ratzinger, along with the rest of his seminary class, is drafted into the Flak [anti-aircraft corps]. He is still allowed to attend classes at the Maximilians-Gymnasium in Munich three days a week.

1944

September: Having reached military age, Ratzinger is released from the Flak and returns home, only to be drafted into labor detail under the infamous Austrian Legion (“fanatical ideologues who tyrannized us without respite”).

November: Ratzinger undergoes basic training with the German infantry. Due to illness he finds himself exempt from most of the rigors of military duty.

1945

Spring (end of April or beginning of May): As the Allied front draws closer, Ratzinger deserts the army and heads home to Traunstein. When the Americans finally arrive at his village, they choose to establish their headquarters in the Ratzinger house. Josef is identified as a German soldier and incarcerated in a POW camp.

June 19: Ratzinger is released and returns home to Traunstein, followed by his brother Georg in July.

November: Ratzinger and his brother Georg re-enter the seminary.

1947

Ratzinger enters the Herzogliches Georgianum, a theological institute associated with the University of Munich.

1951

June 29: Georg and Josef Ratzinger are ordained into the priesthood by Cardinal Faulhaber, in the Cathedral at Freising, on the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

1953

July: Ratzinger receives his doctorate in theology from the University of Munich. In connection with his doctoral studies he produces his first important work: Volk und Haus Gottes in Augustins Lehre von der Kirche [People and House of God in Augustine’s doctrine of the Church].

Ratzinger devotes his Habilitationsschrift — book-length contribution to original research in order to teach at the university level — to Bonaventure’s theology of history and revelation.

1959

April 15: Ratzinger begins lectures as full professor (one holding a chair) of fundamental theology at the University of Bonn.

August 23: Ratzinger’s father passes away.

1962-65

Ratzinger is present during all four sessions of the Second Vatican Council as a peritus, or chief theological advisor to Cardinal Josef Frings of Cologne, Germany.

1963

Ratzinger moves to the University of Münster.

Dec. 16: Ratzinger’s mother passes away.

1966

Ratzinger takes a second chair in dogmatic theology at the University of Tübingen. His appointment is vigorously supported and secured by fellow professor Hans Küng. Ratzinger had initially met Küng in 1957 at a congress of dogmatic theologians in Innsbruck, after recently reviewing Küng’s doctoral work on Karl Barth. Says Ratzinger:

I had many questions to ask of this book because, although its theological style was not my own, I had read it with pleasure and gained respect for its author, whose winning oppenness and straightforwardness I quite liked. A good personal relationship was thus established, even if soon after . . . a rather serious argument began between us about the theology of the council. [Milestones, p. 135]

1968

A wave of student uprisings sweeps across Europe, and Marxism quickly becomes the dominant intellectual system at Tübingen, indoctrinating not only his students but many of the faculty as well. Witnessing the subordination of religion to Marxist political ideology, Ratzinger observes:

There was an instrumentalization by ideologies that were tyrannical, brutal, and cruel. That experience made it clear to me that the abuse of faith had to be resisted precisely if one wanted to uphold the will of the Council [Salt of the Earth].

1969

Scandalized by his encounter with radical ideology at Tübingen, Ratzinger moves back to Bavaria to take a teaching position at the University of Regensburg. He eventually becomes dean and vice president and later, theological advisor to the German bishops.

Two of his most prominent students in these years was the Dominican Christoph Schönborn, who would later become editor of the Catechism of the Catholic Church and cardinal archbisohp of Vienna, and Fr. Joseph Fessio SJ, who would found Ignatius Press.

1972

Ratzinger, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Henry De Lubac and others launch the Catholic theological journalCommunio, a quarterly review of Catholic theology and culture.

1977

On July 24, 1976, Cardinal Julius Dopfner of Munich dies. On March 24, 1977, Ratzinger is appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising by Pope Paul IV. He is urged by his confessor to accept the office, and is consecrated May 28, the vigil of Pentacost. Ratzinger chooses as his episcopal motto the phrase from the third letter of John, “Co-Worker of the Truth,” reasoning:

For one, it seemed to be the connection between my previous task as teacher and my new mission. Despite all the differences in modality, what is involved was and remains the same: to follow truth, to be at its service. And because in today’s world the theme of truth has all but disappeared, because truth appears too great for man, and yet everything falls apart if there is no truth. [Milestones, p. 153].

June 27 – Ratzinger is elevated to Cardinal of Munich by Pope Paul VI.

1980

Ratzinger is named by Pope John Paul II to chair the special Synod on the Laity. Shortly after, the pope asks him to head the Congregation for Catholic Education. Ratzinger declines, feeling he shouldn’t leave his post in Munich too soon.

1981

On November 25, Ratzinger accepts Pope John Paul II’s invitation to take over as Prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Of this acceptance, Peter Seewald would write:

“In particular, his appointment as a prefect [of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith] was an act of sheer obedience to the Pope. Wojtoyla wanted him. And Ratzinger did not stand a chance. Especially not after he had already eluded the call twice with threadbare arguments. The third time it was an order.” (Benedict XVI: An Intimate Portrait

)

1986

On July 10, Pope John Paul II appointed Cardinal Ratzinger head of a 12-member commission responsible for drafting the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The text was released in French in 1992 and in English in 1994.

1998

On November 6, Ratzinger is elected vice dean of the College of Cardinals.

2002

On November 30, The Holy Father, Pope John Paul II, approved his election, by the order of cardinal bishops, as dean of the College of Cardinals.

2005

April 8: Ratzinger precides over the funeral of Pope John Paul II.

April 18: Speaks about the dangers of relativism at a Mass before the opening of the conclave.

April 19, Cardinal Ratzinger is elected Bishop of Rome on the fourth ballot of the conclave, and takes the name Benedict XVI.

“One is very happy not to become Pope. No one has ever shoved his way forward to the Holy See.” – Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, 1978. (As quoted by Peter Seewald in Benedict XVI: An Intimate Portrait.

________________________________________________________________

A very conservative Biography of Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) above

now another view of his life from wikipedia

__________________________________________

Pope Benedict XVI

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Benedict XVI

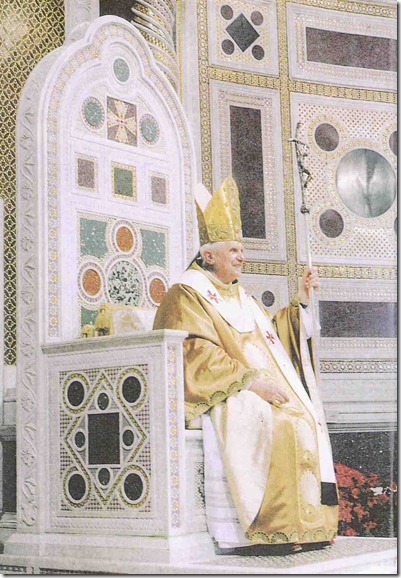

The Pope during a general audience in 2010

Pope Benedict XVI (Latin: Benedictus PP. XVI; Italian: Benedetto XVI; German: Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger on 16 April 1927) is the 265th and current Pope,[1] by virtue of his office of Bishop of Rome, the Sovereign of the Vatican City State and the head of the Roman Catholic Church. He was elected on 19 April 2005 in a papal conclave, celebrated his Papal Inauguration Mass on 24 April 2005, and took possession of his cathedral, the Basilica of St. John Lateran, on 7 May 2005. A native of Bavaria, Pope Benedict XVI has both German and Vatican citizenship. He succeeded John Paul II.

After a long career as an academic, serving as a professor of theology at various German universities (he formally remains a professor at the University of Regensburg), he was appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising and cardinal by Pope Paul VI in 1977. In 1981, he settled in Rome when he became Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, one of the most important offices of the Roman Curia. At the time of his election as Pope, he was also Dean of the College of Cardinals, and as such the primus inter pares among the cardinals.

Like his predecessor, Benedict XVI is theologically conservative and his teaching and prolific[2] writings defend traditional Catholic doctrine and values. During his papacy, Benedict XVI has advocated a return to fundamental Christian values to counter the increasedsecularisation of many developed countries. He views relativism’s denial of objective truth, and the denial of moral truths in particular, as the central problem of the 21st century. He teaches the importance of both the Catholic Church and an understanding of God‘s redemptive love. He has reaffirmed the “importance of prayer in the face of the activism and the growing secularism of many Christians engaged in charitable work.”[3] Pope Benedict has also revived a number of traditions including elevating the Tridentine Mass to a more prominent position.[4]

Pope Benedict is the founder and patron of the Ratzinger Foundation, a charitable organisation, which makes money from the sale of his books and essays in order to fund scholarships and bursaries for students across the world.[5]

Overview

Pope Benedict XVI at a private audience on 20 January 2006

Benedict XVI was elected Pope at the age of 78. He is the oldest person to have been elected Pope since Pope Clement XII (1730–40). He had served longer as a cardinal than any Pope since Benedict XIII (1724–30). He is the ninthGerman Pope, the eighth having been the Dutch-German Pope Adrian VI (1522–23) from Utrecht. The last Pope named Benedict was Benedict XV, an Italian who reigned from 1914 to 1922, during World War I (1914–18).

Born in 1927 in Marktl, Bavaria, Germany, Ratzinger had a distinguished career as a university theologian before being appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising by Pope Paul VI (1963–78). Shortly afterwards, he was made a cardinal in the consistory of 27 June 1977. He was appointed Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith by Pope John Paul II in 1981 and was also assigned the honorific title of the cardinal bishop of Velletri-Segni on 5 April 1993. In 1998, he was elected sub-dean of the College of Cardinals. And on 30 November 2002, he was elected dean, taking, as is customary, the title of Cardinal bishop of the suburbicarian diocese of Ostia. He was the first Dean of the College elected Pope since Paul IV (1555–59) and the first cardinal bishop elected Pope since Pius VIII (1829–30).

Even before becoming Pope, Ratzinger was one of the most influential men in the Roman Curia, and was a close associate of John Paul II. As Dean of the College of Cardinals, he presided over the funeral of John Paul II and over the Mass immediately preceding the 2005 conclave in which he was elected. During the service, he called on the assembled cardinals to hold fast to the doctrine of the faith. He was the public face of the church in the sede vacante period, although, technically, he ranked below the Camerlengo in administrative authority during that time. Like his predecessor, Benedict XVI affirms traditional Catholic doctrine.

In addition to his native German, Benedict XVI fluently speaks French and Italian. He also has a very good command of Latin and speaks English and Spanish adequately. Furthermore, he has some knowledge of Portuguese. He can read Ancient Greek and biblical Hebrew.[6] He has stated that his first foreign language is French. He is a member of several scientific academies, such as the French Académie des sciences morales et politiques. He plays the piano and has a preference for Mozart and Bach.[7]

Early life: 1927–51

Early life of Pope Benedict XVI

Marktl am Inn, the house where Benedict XVI was born. The building still stands today.

Joseph Alois Ratzinger was born on 16 April, Holy Saturday, 1927, at Schulstraße 11, at 8:30 in the morning in his parents’ home in Marktl, Bavaria, Germany. He was baptised the same day. He was the third and youngest child ofJoseph Ratzinger, Sr., a police officer, and Maria Ratzinger (née Peintner). His mother’s family was originally from South Tyrol (now in Italy). Pope Benedict XVI’s brother, Georg Ratzinger, a priest and former director of the Regensburger Domspatzen choir, is still alive. His sister, Maria Ratzinger, who never married, managed Cardinal Ratzinger’s household until her death in 1991. Their grand-uncle was the German politician Georg Ratzinger.

At the age of five, Ratzinger was in a group of children who welcomed the visiting Cardinal Archbishop of Munich with flowers. Struck by the Cardinal’s distinctive garb, he later announced the very same day that he wanted to be a cardinal.

Ratzinger attended the elementary school in Aschau am Inn, which was renamed in his honour in 2009.[8]

Following his 14th birthday in 1941, Ratzinger was conscripted into the Hitler Youth — as membership was required by law for all 14-year old German boys after December 1939[9] — but was an unenthusiastic member who refused to attend meetings, according to his brother.[10] In 1941, one of Ratzinger’s cousins, a 14-year-old boy with Down syndrome, was taken away by the Nazi regime and killed during the Aktion T4 campaign of Nazi eugenics.[11] In 1943, while still in seminary, he was drafted into the German anti-aircraft corps as Luftwaffenhelfer.[10] Ratzinger then trained in the German infantry.[12] As the Allied front drew closer to his post in 1945, he deserted back to his family’s home in Traunstein after his unit had ceased to exist, just as American troops established their headquarters in the Ratzinger household.[13] As a German soldier, he was put in a POW camp but was released a few months later at the end of the war in the summer of 1945.[13] He reentered the seminary, along with his brother Georg, in November of that year.

Following repatriation in 1945, the two brothers entered Saint Michael Seminary in Traunstein, later studying at the Ducal Georgianum (Herzogliches Georgianum) of the Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich. They were both ordained in Freising on 29 June 1951 by Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber of Munich. Ratzinger recalled:

…at the moment the elderly Archbishop laid his hands on me, a little bird — perhaps a lark — flew up from the altar in the high cathedral and trilled a little joyful song.[14]

Ratzinger’s 1953 dissertation was on St. Augustine and was entitled “The People and the House of God in Augustine’s Doctrine of the Church.” His Habilitation (which qualified him for a professorship) was on Bonaventure. It was completed in 1957 and he became a professor of Freising College in 1958.

Pre-papal career

Academic career: 1951–77

Ratzinger became a professor at the University of Bonn in 1959; his inaugural lecture was on “The God of Faith and the God of Philosophy”. In 1963, he moved to the University of Münster.

During this period, Ratzinger participated in the Second Vatican Council (1962–65). Ratzinger served as a peritus (theological consultant) to Cardinal Frings of Cologne. He was viewed during the time of the Council as a reformer, cooperating with theologians like Hans Küng and Edward Schillebeeckx. Ratzinger became an admirer of Karl Rahner, a well-known academic theologian of the Nouvelle Théologie and a proponent of church reform.

In 1966, Joseph Ratzinger was appointed to a chair in dogmatic theology at the University of Tübingen, where he was a colleague of Hans Küng. In his 1968 book Introduction to Christianity, he wrote that the pope has a duty to hear differing voices within the Church before making a decision, and he downplayed the centrality of the papacy. During this time, he distanced himself from the atmosphere of Tübingen and the Marxist leanings of the student movement of the 1960s that quickly radicalised, in the years 1967 and 1968, culminating in a series of disturbances and riots in April and May 1968. Ratzinger came increasingly to see these and associated developments (such as decreasing respect for authority among his students) as connected to a departure from traditional Catholic teachings.[15] Despite his reformist bent, his views increasingly came to contrast with the liberal ideas gaining currency in theological circles.[16]

Some voices, among them Hans Küng, deem this a turn towards Conservatism, while Ratzinger himself said in a 1993 interview, “I see no break in my views as a theologian [over the years]”.[17] Ratzinger has continued to defend the work of the Second Vatican Council, including Nostra Aetate, the document on respect of other religions, ecumenism and the declaration of the right to freedom of religion. Later, as the Prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger most clearly spelled out the Catholic Church’s position on other religions in the 2000 document Dominus Iesus which also talks about the Roman Catholic way to engage in ecumenical dialogue.

During his years at Tübingen University, Ratzinger publicised articles in the reformist theological journal Concilium, though he increasingly chose less reformist themes than other contributors to the magazine such as Hans Küng and Edward Schillebeeckx.

In 1969, he returned to Bavaria, to the University of Regensburg. He founded the theological journal Communio, with Hans Urs von Balthasar, Henri de Lubac, Walter Kasper and others, in 1972. Communio, now published in seventeen languages, including German, English and Spanish, has become a prominent journal of contemporary Catholic theological thought. Until his election as Pope, he remained one of the journal’s most prolific contributors. In 1976, he suggested that the Augsburg Confession might possibly be recognised as a Catholic statement of faith.[18][19]

Archbishop of Munich and Freising: 1977–82

Palais Holnstein in Munich, the residence of Benedict as Archbishop of Munich and Freising

On 24 March 1977, Ratzinger was appointed Archbishop of Munich and Freising. He took as his episcopal motto Cooperatores Veritatis (Co-workers of the Truth) from 3 John 8, a choice he comments upon in his autobiographical work, Milestones. In the consistory of the following 27 June, he was named Cardinal-Priest of Santa Maria Consolatrice al Tiburtino by Pope Paul VI. By the time of the 2005 Conclave, he was one of only 14 remaining cardinals appointed by Paul VI, and one of only three of those under the age of 80. Of these, only he and William Wakefield Baum took part in the conclave.[20]

Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith: 1981–2005

Main article: Joseph Ratzinger as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

On 25 November 1981, Pope John Paul II named Ratzinger Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly known as the “Sacred Congregaton of the Holy Office,” the historical Inquisition. Consequently, he resigned his post at Munich in early 1982. He was promoted within the College of Cardinals to become Cardinal Bishop of Velletri-Segni in 1993, was made the College’s vice-dean in 1998 and dean in 2002.

In office, Ratzinger fulfilled his institutional role, defending and reaffirming Catholic doctrine, including teaching on topics such as birth control, homosexuality, and inter-religious dialogue. Leonardo Boff, for example, was suspended, while others were censured. Other issues also prompted condemnations or revocations of rights to teach: for instance, some posthumous writings of Jesuit priest Anthony de Mello were the subject of a notification. Ratzinger and the Congregation viewed many of them, particularly the later works, as having an element of religious indifferentism (i.e., Christ was “one master alongside others”).

The Congregation is best known for its authority over the teaching of Church doctrine, but it also has jurisdiction over other matters, including cases involving the seal of the confessional, clerical sexual misconduct and other matters, in its function as what amounts to a court. In his capacity as Prefect, Ratzinger’s 2001 letter De delictis gravioribus which clarified the confidentiality of internal Church investigations, as defined in the 1962 document Crimen Sollicitationis, into accusations made against priests of certain crimes, including sexual abuse, became a target of controversy during the sex abuse scandal.[21] While bishops hold the secrecy pertained only internally, and did not preclude investigation by civil law enforcement, the letter was often seen as promoting a coverup.[22] The Pope was accused in a lawsuit of conspiring to cover up the molestation of three boys in Texas, but sought and obtaineddiplomatic immunity from prosecution.[23]

On 12 March 1983, Ratzinger as prefect and cardinal notified the lay faithful and the clergy that archbishop Pierre Martin Ngo Dinh Thuc had incurred the excommunication latae sententiae for illicit episcopal consecrations without the apostolic mandate.

In 1997, when he turned 70, Ratzinger asked the pope John Paul II for permission to leave the Congregation of Doctrine of Faith and to become an archivist in the Vatican Secret Archives and a librarian in the Vatican Library, but the pope refused such permission.[24][25

_________________________________________________________________

We need a little more info on his family heritage as his father views towards the National Socialist German Workers Party(NAZI’S) caused the family some hardship so was he a NAZI OR NOT

Joseph Ratzinger, Sr.

Joseph Ratzinger, Sr. (March 6, 1877 – August 25, 1959) was a German civil servant, policeman, and the father of Pope Benedict XVI (birth name Joseph Alois Ratzinger), and Georg Ratzinger; he was also a nephew of the German politician Georg Ratzinger.

Joseph Ratzinger and his wife Maria had three children in all (the second being Maria Ratzinger), of whom Joseph A. Ratzinger was the youngest.

Service record

Joseph Ratzinger, Sr., served in the Bavarian Landespolizei for several years as a rural policeman.

Various sources state that the Ratzingers’ views towards the National Socialist German Workers Party caused the family some hardship, including the family having to move several times in the 1930s. There is no evidence, however, that Joseph Ratzinger, Sr., was ever arrested for anti-Nazi tendencies. He continued to serve in the police even after such events as the Night of the Long Knives and the passing of the Nuremberg Laws.

In 1936, Joseph Ratzinger, Sr., became a member of the Ordnungspolizei after all the police forces of Nazi Germany were absorbed into the SS.

Retirement

In 1937, Ratzinger retired from the police at an early age of 60 years old, and went to live in Traunstein, a small Bavarian district town.

From this point Ratzinger apparently had no further substantial problems with the Nazi Party. Nevertheless, even late into World War II, most sources agree that Joseph Ratzinger, Sr. remained sternly anti-Nazi, refusing to allow his children to join the Hitler Youth, until threats from political officers made him succumb.

Joseph Ratzinger, Sr. lived the rest of his life in rural Bavaria. He lived to see his sons become priests in the 1950s, but died at the age of 82, decades before the election of his son and namesake Joseph as His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI.

________________________________________________________

We must find out more about this police force he worked for the Ordnungspolizei

The Ordnungspolizei or Orpo

The Ordnungspolizei or Orpo (literally: order police) were the uniformed regular police force in Nazi Germany between 1936 and 1945. It was increasingly absorbed into the Nazi police system. Owing to their green uniforms, they were also referred to as Grüne Polizei (green police). The Orpo was established as a centralized organisation uniting the municipal, city, and rural uniformed forces that had been organised on a state-by-state basis. Eventually the Orpo embraced virtually all of the Third Reich’s law-enforcement and emergency response organizations, including fire brigades, coast guard, civil defence, and even night watchmen.

History

On 17 June 1936, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was named Chef der Deutschen Polizei im Reichsministerium des Innern (Chief of German Police in the Interior Ministry) after Hitler announced a decree that was to “unify the control of Police duties in the Reich”.[2] Traditionally, law enforcement in Germany had been a state and local matter. In this role, Himmler was nominally subordinate to Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick. However, the decree effectively subordinated the police to the SS, making it virtually independent of Frick’s control. Himmler gained authority as all of Germany’s uniformed law enforcement agencies were amalgamated into the new Ordnungspolizei, whose main office became populated by officers of the SS.

The police were divided into the Ordnungspolizei (Orpo or regular police) and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo or security police), which had been established in June 1936.[3] The Orpo assumed duties of regular uniformed law enforcement while the SiPo consisted of the secret state police (Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo) and criminal investigation police (Kriminalpolizei or Kripo). The Kriminalpolizei was a corps of professional detectives involved in fighting crime and the task of the Gestapo was combating espionage and political dissent. On 27 September 1939, the SS security service, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and the SiPo were folded into the Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA).[4] The RSHA symbolized the close connection between the SS (a party organization) and the police (a state organization).

Generalmajor der Ordnungspolizei und SS-Brigadefuhrer Wilhelm Fritz von Roettig was the first general to be killed in World War II, in Opoczno, Poland on 10 September 1939.

The Order Police played a central role in carrying out the Holocaust, as stated by Professor Browning: It is no longer seriously in question that members of the German Order Police, both career professionals and reservists, in both battalion formations and precinct service or Einzeldienst, were at the center of the Holocaust, providing a major manpower source for carrying out numerous deportations, ghetto-clearing operations, and massacres.[5]

Organization

Orpo Chief Kurt Daluege in 1933, as a general in the Prussian Landespolizei.

The Orpo was under the control of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler who was the Chef der Deutschen Polizei im Ministerium des Innern. It was initially commanded by SS-Oberstgruppenführer und Generaloberst der Polizei Kurt Daluege. But in 1943, Daluege had a massive heart attack and was removed from duty. He was replaced by SS-Obergruppenführer und General der Waffen-SS und der Polizei Alfred Wünnenberg, who served until the end of the war.

By 1941, the Orpo had been divided into the following offices covering every aspect of German law enforcement:

Troops from the SS Police Battalions load Jews into boxcars at Marseille, France in January 1943.

Police Battalions

Ordnungspolizei conducting a raid (razzia) in Cracow’s Jewish Ghetto, January 1941.

Between 1939 and 1945, the Ordnungspolizei also maintained separate military formations, independent of the main police offices within Germany. The first such formations were the Police Battalions (SS-Polizei-Bataillone), for various auxiliary duties outside of Germany, including anti-partisan operations, construction of defense works (i.e. Atlantic Wall), and support of combat troops.[6] Specific duties varied widely from unit to unit from one year to another.[7] Generally, the SS Polizei units were not directly involved in combat.[8] Some Police Battalions were primarily focused on traditional security roles of an occupying force while others were directly involved in the Holocaust. This latter role was obscured in the immediate aftermath of World War II, both by accident and by deliberate obfuscation, when most of the focus was on the better-known Einsatzgruppen (“Operational groups”) who reported to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA — Reich Main Security Office) under Reinhard Heydrich.[9]

The Police Battalions consisted of approximately 500 men armed with light infantry weapons. The battalions were originally numbered in series from 1 to 325, but in February 1943 were renamed and renumbered from 1 to about 37[6] to distinguish fromSchutzmannschaft, auxiliary police battalions recruited from local population in German-occupied areas.[8] The Police Battalions were organizationally and administratively under Chief of Police Kurt Daluege but operationally they were under the authority of regional SS- und Polizeiführer (SS and Police Leaders), who reported up a separate chain of command, bypassing Daluege, directly to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler.[10] While these units were similar to Waffen-SS divisions, they were not part of the Waffen-SS and should not be confused with the 4th SS Polizei Division.[6]

During the invasion of Poland in 1939, Police Battalions committed atrocities against both the Catholic and the Jewish populations[11] and as security forces patrolled the perimeters of the Jewish ghettos in Poland (SS, SD, and in some cases the Criminal Police were responsible for internal ghetto security issues in conjunction with Jewish ghetto administration[12]). Starting in 1941 Police Battalions and local Order Police units helped to transport Jews from the ghettos in both Poland and the USSR (and elsewhere in occupied Europe) to the concentration and extermination camps, as well as operations to hunt down and kill Jews outside the ghettos.[13]

Operating both independently and in conjunction with the Einsatzgruppen, Police Battalions were also an integral part of the “Final Solution” in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union which began on 22 July 1941. Police Battalions, whether as part of Police Regiments or as separate units or reporting directly to the local SS-und-Polizeiführer were part of the first and second waves of killing in 1941–2 in the USSR and also in killing operations in Poland.[14] Police Battalion involvement in direct killing operations are responsible for at least 1 million deaths.[15]

The Order Police were one of the two primary sources from which the Einsatzgruppen drew personnel in accordance with manpower needs (the other being the Waffen-SS).[16]

The majority of police battalions formed 28 Police Regiments as of 1942, many of which saw combat on the Eastern Front during the retreat of the German army.

The regular military police of the Wehrmacht were separate from the Ordnungspolizei.

_________________________________________

Well this police force was definitely a hard core part of the NAZI War Machine. The Pope was a Hitler Youth lets look into that now

__________________________________________

Allegations against Pope Benedict XVI

In his 1996 autobiography Salt of the Earth, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) revealed that he was a member of Hitler Youth when he was 14 years old. The disclosure is not unexpected since during World War II, membership was mandatory for almost every teenage male in Germany. However, in a May 2009 trip to Israel, Benedict’s spokesman, Father Federico Lombardi told reporters that Ratzinger was never in the Hitler Youth, actually being in the Luftwaffe as an air force assistant.[12] According to the Pope’s brother, Monsignor Gregor Ratzinger, Josef was automatically placed on the Hitler Youth membership rolls on turning 14, as was required by law, but “did not attend meetings.”[13] In 1943 Ratzinger was conscripted into the Flakhelfer, teenage boys who assisted the crews of Luftwaffe antiaircraft guns; he eventually deserted and made his way to the American lines.[14] The Ratzinger family, according to those who knew them, were very religious and hated the Nazi regime.[15]

_________________________________

There’s fresh allegations emerging that former Hitler Youth and Nazi anti-aircraft gunner Pope Benedict XVI (pictured above) failed to take action against a priest who admitted molesting deaf children. A US newspaper claims that the Prussian Pontiff, when he was previously Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, was in charge of the church’s doctrinal enforcement institution, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in the late 1990s. The newspaper has obtained papers relating to the case which it says Roman Catholic church officials had tried to keep private. The accusation is that Vatican officials including the future Pope declined to discipline or defrock the priest, Father Lawrence Murphy, who was a teacher at a school for deaf children in Wisconsin for 24 years and was suspected of sexually abusing up to 200 boys. Paedophilia, corruption, perversion, cover-ups and hypocrisy. Same old, same old.

________________________________

Pope says Jews not responsible for Jesus’ death

Updated Thu Mar 3, 2011 10:04am AEDT

Pope Benedict XVI has personally exonerated Jews of allegations they were responsible for Jesus Christ’s death.

The Pope makes his complex theological and biblical evaluation in a section of the second volume of his book, Jesus of Nazareth, which will be published next week.

In it, he repudiates the concept of collective guilt that has haunted Christian-Jewish relations for centuries.

“Now we must ask: Who exactly were Jesus’s accusers?” the Pope asks, adding that the gospel of St John simply says it was “the Jews”.

“But John’s use of this expression does not in any way indicate – as the modern reader might suppose – the people of Israel in general, even less is it ‘racist’ in character,” he writes.

“After all John himself was ethnically a Jew, as were Jesus and all his followers. The entire early Christian community was made up of Jews.”

Pope Benedict says the reference was to the “Temple aristocracy,” who wanted Jesus condemned to death because he had declared himself king of the Jews and had violated Jewish religious law.

He concludes that the “real group of accusers” were the Temple authorities and not all Jews of the time.

The Roman Catholic Church officially repudiated the idea of collective Jewish guilt for Christ’s death in a major document by the Second Vatican Council in 1965.

Major step forward

Elan Steinberg, vice-president of the American Gathering of Holocaust Survivors and their Descendants, welcomed the Pope’s words.

“This is a major step forward. This is a personal repudiation of the theological underpinning of centuries of anti-Semitism,” he said.

“This Pope has categorically stated that the canard that Jews were Christ killers is a gross theological lie and this is most welcome in view of the setbacks that we have seen in the past few years.”

The question of Jewish responsibility for Christ’s death has haunted Christian-Jewish relations for nearly 2,000 years.

Benedict, elected in 2005, has had his share of problems in Christian-Jewish relations.

In 2009, he decided to advance wartime Pope Pius XII on the path towards sainthood by recognising his “heroic virtues”.

Many Jews accuse Pius, who reigned from 1939 to 1958, of having turned a blind eye to the Holocaust. The Vatican says he worked quietly behind the scenes because speaking out would have led to Nazi reprisals against Catholics and Jews in Europe.

Jews responded angrily last year when the Pope said in another book that Pius was “one of the great righteous men and that he saved more Jews than anyone else”.

Jews have asked that the process that could lead to making Pius a saint be frozen until after all the Vatican archives from the period are opened and studied.

Earlier in 2009, many Jews and others were outraged when Benedict lifted the excommunication of traditionalist Bishop Richard, who caused an international uproar by denying the full extent of the Holocaust and claiming no Jews were killed in gas chambers.

_____________________________________________________

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI was once dubbed “God’s rottweiler” but his pontificate has seen him frequently forced on to the defensive.

Previously known as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the professorial pianist was looking forward to retirement when Pope John Paul II died in 2005. He has said he never wanted to be Pope.

But he took the helm as one of the fiercest storms the Catholic Church has faced in decades – the scandal of child sex abuse by priests – was breaking.

The flood of allegations, lawsuits and official reports into clerical abuse reached a peak in 2009 and 2010.

‘Sin within’

The most damaging claims for the Church have been that local dioceses – or even the Vatican itself – were complicit in the cover-up of many of the cases, prevaricating over the punishment of paedophile priests and sometimes moving them to new postings where they continued to abuse.

While some senior Vatican figures initially lashed out at the media or alleged an anti-Catholic conspiracy, the Pope has insisted that the Church accept its own responsibility, pointing directly to “sin within the Church”.

He has met and issued an unprecedented apology to victims, promised action and made clear that bishops must report abuse cases to the local authorities.

Continue reading the main story

“Start Quote

If Benedict had not been Pope, he would have been a university professor”

John L AllenUS Vatican expert

As Cardinal Ratzinger, he spent 24 years as one of the senior figures in the Vatican, heading the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – once known as the Holy Office of the Inquisition.

It made him John Paul II’s “enforcer”, and played to his passion for Catholic doctrine.

His high office gave him ultimate oversight of a number of clerical abuse cases.

Critics say he did not grasp the gravity of the crimes involved, allowing them to languish for years without proper attention – or even that he deliberately subordinated the victims’ welfare to that of the Church itself.

He has never publicly given his own version of events.

His backers, however, say he has done more than any other pope to confront abuse.

Shortly before his election in 2005, he lamented: “How much filth there is in the Church, and even among those… in the priesthood.”

And one of his first acts as Pope was to banish a former Vatican favourite, Father Marcial Maciel, whose sexual and criminal exploits were starting to come to light.

Formative experiences

Joseph Ratzinger was born into a traditional Bavarian farming family in 1927, although his father was a policeman.

The eighth German to become Pope, he speaks many languages and has a fondness for Mozart and Beethoven.

Benedict has carried his love of fine clothes to the Vatican

He was said to have admired the red robes of the visiting archbishop of Munich when he was just five and carried his love of finery to the Vatican, where he has re-introduced papal hats not seen in decades.

At the age of 14, he joined the Hitler Youth, as was required of young Germans of the time.

World War II saw his studies at Traunstein seminary interrupted when he was drafted into an anti-aircraft unit in Munich.

He deserted the German army towards the end of the war and was briefly held as a prisoner-of-war by the Allies in 1945.

The Pope’s conservative, traditionalist views were intensified by his experiences during the liberal 1960s.

He taught at the University of Bonn from 1959 and in 1966 took a chair in dogmatic theology at the University of Tuebingen.

However, he was appalled at the prevalence of Marxism among his students.

In his view, religion was being subordinated to a political ideology that he considered “tyrannical, brutal and cruel”.

He would later be a leading campaigner against liberation theology, the movement to involve the Church in social activism, which for him was too close to Marxism.

Mild and humble

In 1969 he moved to Regensburg University in his native Bavaria and rose to become its dean and vice-president.

He was named cardinal of Munich by Pope Paul VI in 1977.

At the age of 78, Joseph Ratzinger was the oldest cardinal to become Pope since Clement XII was elected in 1730.

It was always going to be difficult living up to his charismatic predecessor.

As cardinal, Joseph Ratzinger was a prominent figure under John Paul II

“If John Paul II had not been Pope, he would have been a movie star; if Benedict had not been Pope, he would have been a university professor,” wrote US Vatican expert John L Allen.

“No surprise that John Paul took the world by storm, while Benedict stands a bit off the beaten path.”

Benedict is described by those who know him as laidback, with a mild and humble manner, but with a strong moral core.

One cardinal put it another way, calling him “timid but stubborn”.

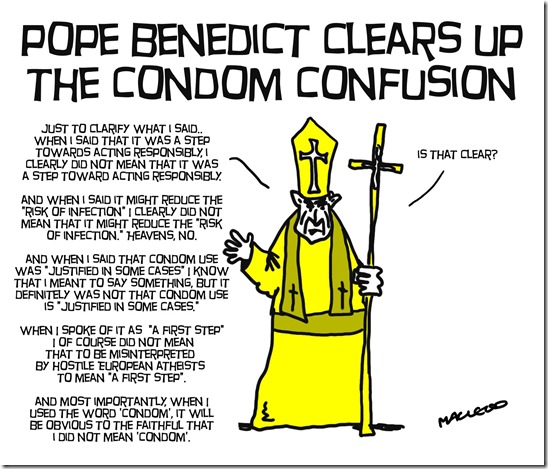

He has a reputation as a theological conservative, taking uncompromising positions on homosexuality, women priests and contraception.

He espouses Christian compassion – speaking out recently against Roma deportations in France, and against human rights abuses in China and elsewhere.

He criticised the US-led war in Iraq, and has called for more urgency in protecting the environment and fighting the “scandal” of poverty.

PR disasters

A central theme of his papacy has been his defence of fundamental Christian values in the face of what he sees as moral decline across much of Europe.

But he has confounded those who expected him to appoint hard-line traditionalists to key posts, choosing instead many who occupy the Church’s centre ground.

However, questions have been raised about those who advise him, after a series of public relations disasters.

Muslims took offence when, in 2006, he quoted a 14th Century Byzantine emperor who said the Prophet Muhammad had brought the world only “evil and inhuman” things.

Then Jews were taken aback when a breakaway group of bishops was welcomed back into the Church fold, including one who was found to be a Holocaust-denier.

Benedict visited Auschwitz in 2006 to pray for the dead of the Holocaust

Thus the Pope’s avowed intention of improving inter-faith relations was seriously undermined.

And he even offended fellow Christians, by making it easier for Anglicans to defect to the Catholic Church without discussing the matter with the Church of England beforehand.

At the height of the abuse scandal, senior cardinals also caused outrage by dismissing some allegations as “idle chatter” and asserting a link between homosexuality and paedophilia.

Vatican watchers said the Holy See appeared to have no media strategy to deal with the crisis, and was starting new fires faster than it could put them out.

But although they threaten to undermine the authority of the Church, Benedict seems unlikely to meet such crises by compromising with the liberal modern world.

He has always believed that the strength of the Church comes from an absolute truth that does not bend with the winds.

That approach disappoints those who feel the Church needs to modernise and despair of his intransigence on priestly celibacy or condoms.

But for his supporters, it is exactly why he is the man to lead the Church through such challenging times.

________________________________________________

Helpless in the Vatican

The Failed Papacy of Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI celebrates mass in memory of John Paul II on the 5th anniversary of his death in Saint Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican on March 29, 2010. The pope’s hesitant treatment of priest sex abuse scandals is expanding into a crisis for the Catholic Church and fueling outrage over his papacy. (AFP)

The pope’s reluctance to take a firm stance on sexual abuse by priests is expanding into a crisis for the Catholic Church and fueling outrage over his papacy. Some Catholics are now even calling on Benedict, who has committed a series of gaffes since becoming pope in 2005, to resign. By SPIEGEL staff.

“Lord!” the man begins. It is night, and the torches cast flickering shadows on the ancient walls. “Your Church often seems like a boat about to sink, a boat taking in water on every side.” It is a somber statement, particularly coming from a senior member of the Catholic Church.

The priest continues, speaking of weeds in the fields of the Lord, and of how much “filth there is in the Church,” the result of priests’ betrayal of God. “The soiled garments and face of your Church throw us into confusion. Yet it is we ourselves who have soiled them! It is we who betray you time and time again.” He beseeches God, saying: “Have mercy on your Church; even within her, Adam continues to fall again and again.”

These were prophetic words. They reflected a bitterness and lack of illusions that could only have been expressed by an experienced cardinal who had exhaustively studied the files outlining the “filth in the Church.”

The speaker was Joseph Ratzinger. He was chastising his own church during the Easter holiday five years ago, in 2005. It was a bitter indictment by a veteran of the Church, who apparently had little hope and was on the verge of retirement. It was meant as a legacy and as a warning, but what Ratzinger did not do was to specify the actual misconduct.

At the Center of the Filth

Five years later, the situation in the Church has caught up with Ratzinger, who is now Pope Benedict XVI. The filth in the Church has seeped out of the secret dossiers and hidden corners of vestries, seminaries and schools and has been brought to light. As the head of the Church, the captain of this battered ship, Ratzinger now finds himself at the center of the filth.

The pope is now confronted with accusations from all over the world, accompanied by increasingly urgent appeals to finally render his ship seaworthy again. The sex abuse cases which were initially a problem only for national bishops’ conferences, particularly in the United States, Ireland and Germany, have merged into a crisis for the entire Catholic Church, a crisis that is now descending upon the Vatican with a vengeance and hitting its spiritual leader hard. Meanwhile that leader seems oblivious to what has happened so suddenly.

In Germany, churchgoers are demanding to know why Benedict has not said a word about the crimes of priests in his native country. Christian Weisner, a senior member of the reform movement “We Are Church,” is deeply disappointed by the pope. Benedict XVI, says Weisner, has “not understood the true scope of the distress.”

Demands for Repentance

The Poles are angry with the pope, because they fear that his inaction in the face of the crisis could harm the reputation of “their” pope, John Paul II, whose beatification they expect to take place soon. “A public mea culpa would have given him credibility in the fight over the purity of the Church,” wrote the Polish daily newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza.

The Irish, to whom Benedict wrote a pastoral letter in which he assigned the responsibility for the abuse cases to local bishops and, in what was not exactly a sign of remorse, to the “secularization of Irish society,” were disappointed in the pope. Writing in the Sunday Tribune, an Irish Sunday newspaper, columnist Maurice O’Connell demanded: “Why, for example, can Benedict not jump on a plane, come to Ireland, and, on Maundy Thursday (as he will be doing in Rome), wash the feet of 12 victims?”

Finally, in the United States, where about 12,000 abuse cases have come to light in the last few decades and the media are already accusing the pope himself of having covered up the scandals, the attorney of one abuse victim even wants to force the pontiff to appear in court. Many Catholics who suffered as a result of the sexual urges of their priests 30 years ago have given up hope that the pope will show any remorse at all. David Clohessy, the national director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), accuses the pope of ignoring the suffering of the victims. “Actions, not words, protect innocent kids and heal wounded victims,” says Clohessy.

Papacy In Jeopardy

Suddenly, the worldwide chorus of outrage seems to be putting the German pope’s entire papacy in jeopardy.

Benedict XVI began his papacy by embarking on a project of reconciliation which went beyond the Church itself. The newly elected pope wanted to rule with the word, and with discourse, not prohibitions. That was what he had been doing for 23 years in his previous position, as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). And now he was suddenly advocating an open, self-confident dialogue on several fronts: with the secular world, with Islam, with the Jews and with the traditionalists within the Church. Perhaps even with the followers of Martin Luther.

Now, after five years in office, Benedict has seen his project fail and himself become a spiritual shepherd lost in a world that no longer understands him. The secular world now views the pope with, at best, indifference, if not downright hostility. The Church’s dialogue with the Jews suffered a serious setback in the wake of the scandal surrounding Holocaust denier Bishop Richard Williamson. An icy silence still predominates in parts of the rabbinate, and the planned beatification of Pius XII, whose role during the Nazi era is controversial, will hardly change that.

Many Muslims have never forgiven Benedict for a lecture he gave in Regensburg in 2006, where he examined the issue of violence and Islam in a bold but ineptly executed move. The speech unleashed a torrent of protests in the Muslim world.

Even radical opponents of reform, such as the Society of St. Pius X (SSPX) and other traditionalists, have not hurried back to Rome, even though the pope has opened all doors for them, declared the Latin mass to be equally valid and reversed the excommunication of SSPX’s bishops. Meanwhile, Benedict’s gesture of reconciliation toward the extreme right fringe has angered more liberal dioceses in Germany and France.

Part 2: Calls for Benedict’s Resignation

Protesters hold placards on March 28, 2010 in London, calling for the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI over abuse scandals involving the Church.

Of course, the office of pope does not exist so that its holder can be loved by the whole world. After Pius IX died in 1881, a number of Rome residents tried to seize the coffin so that they could throw it into the Tiber River. Today, a few days after Easter, only the most devoted pilgrims are rallying around their spiritual leader. The rest of the world, shocked by the sheer scope of the abuse cases, looks to Rome with skepticism, and some are already calling upon Benedict to take responsibility for his sinning priests and resign.

In the Italian magazine MicroMega, Don Paolo Farinella, a Catholic priest, has already written an example of the kind of statement he believes the pope should make to Irish Catholics: “I come to you with empty hands to beg your forgiveness” — for the strictness of the celibacy, for the conditions in seminaries and for the thousands of cases of child abuse. “I will withdraw to a monastery and will spend the rest of my days doing penance for my failure as a priest and pope.”

It hasn’t come to that yet, not by a long shot. Some 80 percent of Germans still cannot imagine Benedict following the example of an almost forgotten pope, Celestine V, who resigned in the 13th century because he no longer felt able to perform his office.

Nevertheless, the question remains as to why nothing seems to go right anymore for this once-celebrated pontiff.

‘A Humble Worker in the Vineyard of the Lord’

It is the tragedy of a man who had set out to write books and, only near the end of his life, was summoned to assume the herculean office at the Vatican. At the beginning of his papacy, Benedict XVI described himself, in all modesty, as “a simple humble worker in the vineyard of the Lord.”

To date, however, Joseph Ratzinger has been more of a hobby gardener in the vineyard, rather than a landscape architect or someone who cuts off fruitless vines.

Benedict XVI lacks his predecessor’s ability to always find the right symbolic gestures. The charismatic John Paul II led the church at the height of the American abuse crisis, but it did not diminish his popularity.

He has incurred the suspicions of the secular world and the skepticism of other religions, but he has not found a way to address this opposition. Again and again, after each new scandal, each misunderstanding and each new blunder, his actions seem forced. He lacks his predecessor’s ability to always find the right symbolic gestures. The charismatic John Paul II led the church at the height of the American abuse crisis, but it did not diminish his popularity. Even before his death, as he allowed the world to participate in his process of dying, crowds flooded into St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City to be close to him.

Of course, what English author G.K. Chesterton wrote in the early 20th century still holds true today. “At least five times,” Chesterton wrote, “the Faith has, to all appearance, gone to the dogs. In each of these five cases, it was the dog that died.”

Some may find comfort in Chesterton’s remark.

Derision for Religion

Nevertheless, many Catholics find their pope’s actions painful to watch, not because they consider him incapable or even unlikeable, but because they cannot look on as this extraordinary man gets in his own way. The members of the “We Are Church” movement, in particular, have turned away from Benedict.

According to a poll conducted for SPIEGEL by pollster TNS Forschung, 73 percent of Germans believe that the pope’s handling of abuse cases in the Catholic Church is “not adequate.”

Following the revelations about clerical misconduct, the disenchantment has, in many places, turned into aggression, malice and, in some cases, cheap derision against all things religious. In the last few weeks, a tone of contempt for the Catholic Church has emerged in online forums throughout Germany.

In one forum, a contributor wrote: “The fact that the Church only admits what it can no longer deny shows that the Vatican only regrets one thing, if anything: the fact that the priests were caught.”

Another contributor wrote: “The institution of the Church is a morally depraved club of old men. One needs to distance oneself from this organization as clearly as possible.”

What’s Wrong with the Church

There is also no lack of recommendations relating to the future of the Church, both from believers and non-believers. Suddenly everyone knows what the Church has done wrong in decades gone by: the celibacy and the exclusion of women from the priesthood; the hierarchy of old men and the persecution of any efforts to liberalize the theology; the blind condemnation of contraception and birth control in the poor regions of the world; the eternal lack of understanding of homosexuality; the mistrust of technology and modern culture; and the constant needling and provocation aimed at the Protestant churches, Judaism and Islam.

Ratzinger the theologian has defended the doctrines and precepts of his church again and again, often cleverly and with exquisite scholarliness. In doing so, he has cited the teachings of the Church fathers, the councils and the entire Holy Scripture.

For a time, he enjoyed the undivided goodwill of the German press. Even Hamburg’s arch-Protestant weekly newspaper Die Zeit softened its otherwise skeptical view of Rome.

Nevertheless, Benedict’s message did not reach its intended audience. The pope lost his close connection to his wards. The master of the word failed to convince the public of the legitimacy of even one of his positions.

This may have something to do with the public — or the positions.

In any event, the Germans’ goodwill toward “their pope” was short-lived. In fact, most of his fellow Germans have long immersed themselves in their own personal belief system. Although they clearly retain the desire for a metaphysical source of comfort when life becomes difficult, they prefer to dispense with the institution and its requirements.

Part 3: ‘Weary of Faith’

Christendom has “grown weary of faith (and) has abandoned the Lord,” as Ratzinger concluded in his prayers for the Stations of the Cross at the Roman Coliseum in 2005. He spoke of the “banal existence of those who, no longer believing in anything, simply drift through life.”

But the pope, this owl-eyed old man with a high voice, simply isn’t as adorable as the Dalai Lama. He lacks the clear message of a Barack Obama. And no one would want to be stuck on a deserted island with one of his German propagandists, let alone be guided through the desert by them.

The days of Vatican chic are over, it seems.

Germany’s flirtation with this man lasted all of two summers. For a time, it was hip to have read Ratzinger. Authors suddenly began making pilgrimages and the culture sections of magazines wondered if it was time for a return of the sacred. Berlin’s upper middle class sent its children to the Canisius College Jesuit high school, convinced that they were guaranteeing their children’s future.

Warning Signs

Nevertheless, the disenchantment quickly set in. The longer Benedict was in office, the clearer it became that he was not interested in the opening up of the Church to the modern world that the public — which had perhaps been fooling itself — had expected of him.

His revival of the traditional Latin mass, the return of the idea of the controversial prayer for the Jews in the Good Friday prayers, the departure from critical biblical research in his book “Jesus of Nazareth” — these were all relatively minor and inconspicuous steps in the direction of a more traditional Church. Observant church insiders, however, quickly recognized their significance as a warning sign.

In Germany, in particular, the mood began shifting beyond the Catholic Church when, in 2007, Benedict offended the country’s 25 million Protestants with a verdict from the Vatican, stating that their denominations could “not be called churches in the real sense.” His message of “dogma instead of dialogue” also offended the Catholic base, which, in many places, had long surpassed Church leaders in their ecumenical efforts. Even the then-leader of German Catholics, Cardinal Karl Lehmann, was clearly against the direction Benedict had taken, and tried to soften it somewhat with his own positions.

‘He Disappointed the World’

Swiss theologian Hans Küng, Ratzinger’s old friend from the days of the Second Vatican Council and later his adversary, soberly concluded that his audience with the pope at the beginning of Benedict’s papacy did not, by a long way, signal a new dawn in the Church. “I had assumed that my invitation was the first in a series of bold acts of which the pope was capable. But he disappointed the world. Since then, he has not issued any further signals of renewal. On the contrary, he has, time and again, taken a step backward from the achievements of the Council.”

In his position as pope, Ratzinger had the chance to strike out in a different direction than in his previous post as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, where he was the Church’s supreme commissioner of faith for almost a quarter century. As Benedict, however, he quickly gambled away this opportunity and slipped back into his old role. Ratzinger has therefore become a prisoner of his biography — to the detriment of the Catholic Church.

Ratzinger’s ‘Rational Adventure’

Joseph Ratzinger was born on April 16, 1927 in the Bavarian village of Marktl am Inn, the son of a police officer. Although money was tight, Joseph and his older brother, Georg, attended high school.

When Joseph, their youngest son, was only in second grade, the parents bought him a missal, the Mass book priests use on the altar. For Ratzinger, religion became what he would later call a “rational adventure.” His Catholicism was never merely incense and naïve faith.

His school registered him for the Hitler Youth, which was unavoidable, but he rarely attended. He was eventually drafted to serve as a child soldier in Munich. He spent the end of the war in a POW camp near the southern German city of Ulm.

Ratzinger was consecrated as a priest in 1951. He only worked in pastoral care for a short time, however, meaning he had little first-hand experience with the everyday worries of the faithful.

Part 4: Traumatic Experiences

Instead, he quickly embarked on a career as a theologian. In 1958, at the age of 31, he became a professor of dogmatic and fundamental theology. In 1962, he served as a theological consultant to the Second Vatican Council, where Ratzinger championed views that were both liberal and critical of the Vatican, views that advocated the individual freedom of a Christian and opposed the Roman Curia’s claim to omnipotence. At the time, Ratzinger argued that the Church had “reins that are far too tight, too many laws, many of which have helped to leave the century of unbelief in the lurch, instead of helping it to redemption.”

After the Council, Ratzinger, together with Hans Küng and Karl Rahner, was considered one of the reformers in the Church. In 1966, he brought his friend Küng to the University of Tübingen in southern Germany as a professor of dogmatic theology. In 1968, Ratzinger and 1,360 other theologians worldwide signed a resolution drafted by Küng, titled “For the Freedom of Theology.”

In the same year, however, Ratzinger had a traumatic experience that explains his thoughts and actions to this day. During the 1968 revolt, he witnessed his students reviling the image of Christ on the cross as a “sadomasochistic glorification of pain” and chanting “Jesus be damned!” during one of his lectures. In a 1983 SPIEGEL interview, he said that it became clear to him in the lecture halls at Tübingen, then under the spell of the great Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch, that the outcome of the Council had been the “opposite” of what had been intended.

Guardian of the Truth

For the 41-year-old cleric, the Tübingen experiences were a deep shock that changed him radically from a cosmopolitan theologian to a timid dogmatist. Since then, the unalterable, God-given truth has meant everything to him. For Ratzinger everything had to be subordinate to this truth.

Ratzinger also believed that the Catholic Church is the guardian of the absolute moral truth. As archbishop of Munich and Freising, Ratzinger had the motto “Cooperatores veritatis” (“Worker of Truth”) embroidered onto his shoulder shawl. As Ratzinger often points out disdainfully, he believes that the notion that truth only reveals itself in fragments to people, including those who believe in God, and that truth is therefore not a fixed variable but takes on different forms in time and space, depending on culture and tradition, is nothing but condemnable “relativism.”

In Ratzinger’s world, man is more of an object than an active subject. Critics of this pope have noticed, again and again, that he comes across as distant and cold, even when he turns to people with deliberate affection. He completely lacks the charisma of palpable brotherly love that John Paul II exuded.

In 1981, John Paul II brought Ratzinger, then an archbishop who had already been elevated to the rank of cardinal, to Rome to head the CDF. At the pope’s request, Ratzinger first turned his attention to Latin America. The Polish pope believed that leftist priests there were trying to lead the faithful astray into Marxist convictions. He pilloried the liberation theologian Leonardo Boff and condemned the movement’s commitment, which was based on theology, to a Church of the poor.

Staunch Crusader

For more than two decades, Cardinal Ratzinger, from his office in Rome, kept watch to ensure that the faithful around the world — including, in particular, the Church’s functionaries, its priests and bishops — toed the line. His soft gestures, shyness and high voice can be deceptive. In truth, Ratzinger is also a staunch crusader.

When Ratzinger became pope, he met with nothing but enthusiasm in the first few months of his papacy. Soon, however, he quickly became the target of criticism. His Regensburg speech in September 2006 provoked Islamists around the world to commit acts of violence against Christians. It was only with difficulty that the Church managed to smooth out the waves of outrage Benedict’s words had triggered. Nevertheless, many still believed that it was all a misunderstanding, and that the learned professor had only expressed himself awkwardly when he said, quoting the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus: “Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman.”

The next scandal came in January 2009, when the pope rehabilitated Holocaust denier Richard Williamson, an excommunicated bishop of the Society of St. Pius X, a reactionary faith group that Benedict XVI was determined to bring back into his church. It was all the more controversial because Benedict is German. For fear of a permanent rift, the pope risked the reputation of Catholicism worldwide.

When Benedict XVI visited Israel a few months later, a trip that was only made possible after a number of pretexts and explanations, his appearance at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial was sharply criticized as being “almost sterile,” “unemotional” and simply “disappointing.” Chief Rabbi Israel Meir Lau had expected to see more human sympathy for the suffering of murdered Jews. Instead, he said, the pope’s speech was “devoid of any compassion, any regret, any pain over the horrible tragedy.” He also criticized the pope for not using the phrase “6 million Jews” in relation to the number of Holocaust victims.

Part 5: The False Life of Man

Ratzinger has always been a shy person. But he came away from his experiences in Tübingen with an insurmountable fear: a fear for the wellbeing of the Church. Ratzinger wrote his dissertation on St. Augustine, the church father who imagined Christ wandering through the world as a stranger, driven by the constant endeavor to work toward a theocracy.

He also took on Augustine’s repression of sensuality, which the church father made socially acceptable in the church in the 4th century, and his pessimism and rejection of the things of this world. It is a way of thinking that assumes that little good can be expected from the world beyond the walls of the Church and the Vatican. It also holds that if there is a true life within the false life of man, it only exists inside the Church, and that only the walls of the Vatican offer protection.

Those days are gone. Today, outrage directed at the Church can no longer be kept within the affected dioceses. The public is also demanding an explanation from the spiritual leader in Rome, particularly as the pope himself was confronted with these problems during his spiritual career. During his time as archbishop of Munich, there was the case of the priest Peter H., which has come back to haunt the pontiff in recent weeks.

The priest had attracted attention in the Diocese of Essen because of child molestation, and the diocese recommended that he undergo therapy under the care of the Archdiocese of Munich. Ratzinger agreed. But after the therapy, his vicar general assigned the man to another parish, allegedly with Ratzinger’s knowledge. Peter H. molested more children in the ensuing years and was only banned from providing pastoral care in 2008. Last week, the Archdiocese of Munich even had to send a priest to the towns of Garching and Bad Tölz to help repair the trail of emotional destruction left by the erring priest.

‘Too Much Failure’

The pope’s most recent pastoral letter on sexual abuse in Ireland was a source of disappointment. “What would it have taken to devote a few sentences to the dramatic developments in Germany?” complained members of the German Catholic youth organization BDKJ. Even the archbishop of Berlin, Cardinal Georg Sterzinsky, made a penitential pilgrimage through the streets of the German capital. “We suffer from the fact that there is too much failure in the church,” Sterzinsky said.

For Ratzinger the man, the world outside the Church and the Vatican, the world of power and the power of the worldly, has always been something sinister. Even during his time as prefect of the CDF, he did not take the trouble to develop the network of supporters considered normal for a senior member of the Church. He was not interested in intrigues and tactical maneuvers. The theology professor, who accepts no contradiction between reason and faith, was always confident in the power of arguments.

He knew that it wouldn’t be easy. “Society hates us because we stand in its way,” he once confided in his biographer, Peter Seewald. Given this mindset, he could not have been truly surprised by the uproar of the past few weeks.

But it has affected him.

‘The Human Flesh’

In particular, it pained Ratzinger that the person who is probably closest to him, his brother Georg, was cast in a bad light. Georg Ratzinger was director of the Regensburger Domspatzen, the cathedral choir in the Bavarian city of Regensburg, from 1964 to 1994. He was strict and sometimes used corporal punishment. Critics allege that Georg Ratzinger must have known about sexual abuse cases in the boarding school associated with the choir.

On his name day, the feast of St. Joseph of Nazareth, Joseph Ratzinger was sitting with his brother Georg in the ceremonial hall of the Palace of the Vatican, the Sala Clementina. The pastoral letter to Irish Catholics had just been signed. The two brothers looked fragile, their white hair slightly tousled. The Henschel Quartet was playing Haydn’s “The Seven Last Words of Our Savior on the Cross.”

“It would have been better to preserve the silence,” the younger of the two brothers, the pope, said after the performance. He was referring to the customary moment of silence after the music ends. But he could not remain silent, and instead spent a full eight minutes talking about doubts and forgiveness and committing oneself to a higher purpose. He spoke about beauty and that difficult material, “the human flesh.” It’s a material which is very foreign to him — and yet it will shape the last years of his papacy.

It was a moving moment, probably one of the few moments in which the pope was not being driven by his official duties.

Part 6: Keeping Quiet about Abuse Cases

As it happens, there are members of the Church who are far more obstinate than Joseph Ratzinger in keeping quiet about cases of sexual abuse.

For example, the case of Father Lawrence Murphy from Milwaukee, who molested about 200 boys at a school for the deaf, was not reported to Rome until 20 years after the last incidence of abuse. Under a strict interpretation of church law, that meant that the statute of limitations had already expired.

Nevertheless, Ratzinger’s CDF supported the initiation of proceedings against Murphy. Ratzinger’s deputy, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, only recommended that the case be dropped after Murphy, who was already fatally ill, had begged for mercy in a letter to Ratzinger.

As prefect of the CDF, Ratzinger urged John Paul II, in 2001, to issue the papal letter known as the “Motu Proprio,” which obligated the church to report all abuse cases to Rome and address them there.

Critics saw this as an attempt to keep the scandals under control and to handle them with the utmost discretion. The Vatican insisted that the requirement of “papal secrecy” was meant solely to protect those involved, and that it never precluded reporting abuse cases to the secular authorities.

The Vatican’s Worst Nightmare

Many Catholics questioned whether this was true. After the issuance of the Motu Proprio, however, all dossiers relating to pedophile priests passed across Ratzinger’s desk. No one in the global Church had a better idea of what was really going on in the seminaries and Catholic institutions. And this is precisely why the Catholic Church could very well face proceedings that could expand into Vatican lawyers’ worst nightmare, and could end in the pope having to answer for the charges of abuse in a secular court.

“I want to know what the Vatican knew and when they knew it,” attorney William McMurry, who is representing three alleged victims of priest sexual abuse in Kentucky, told the Washington Post. Their case has now come before the US District Court in Louisville, and could eventually make it all the way through the courts to the Supreme Court in Washington. The plaintiffs argue that the Vatican can be held responsible for the damage inflicted by its employees. With the suit, the Americans hope to embark on a legal path that seemed off-limits for years: They are determined to assert a direct claim by abuse victims against the Vatican.

Jeff Anderson, an attorney from Minnesota who has represented hundreds of abuse victims since 1983 and has won millions of dollars in compensatory damages for his clients, has been waiting for such an opportunity to come along. In recent weeks, Anderson made headlines worldwide when he turned over documents about the Father Murphy case to the New York Times. Now he is hoping for the biggest conceivable prize: to subpoena the Holy Father himself. “This is a tipping point,” Anderson told the Associated Press. “I came to the stark realization that the problems were really endemic to the clerical culture, and all the problems we are having in the US led back to Rome. And I realized nothing was going to fundamentally change until they did.”

Elaborate Defense Strategy

Although legal experts agree that summoning Benedict XVI to testify before a US court is extremely unlikely, the lengthy legal battle this would entail would be embarrassing enough.

Ratzinger’s church lawyers have already assembled an elaborate defense strategy. They argue that the pope, as the Vatican’s head of state, enjoys immunity against lawsuits in US courts. They also point out that the American bishops who covered up abuse cases are not employees subject to directives from Vatican City.

Ironically, Ratzinger has always advocated that his Church take a tough approach toward sinners in cassocks. For him, the ordination of priests is a central sacrament, an office that entails constant self-examination and strict discipline.

For example, Ratzinger enforced his hard line against the Mexican priest Marcial Maciel Degollado, the founder of the Legion of Christ, a powerful congregation of priests. Maciel Degollado, who died in 2008, allegedly fathered and abused several children.

Despite the many rumors, John Paul II, who deeply respected Maciel Degollado as a servant of God, dedicated a festive mass on St. Peter’s Square to the Mexican priest in 2001. One of Ratzinger’s first actions in his new office as pope, however, was to banish Maciel Degollado to a monastery.

‘Targeted Campaign’

But like the vast majority of bishops in the past (and many today), Ratzinger is also convinced that too much openness only benefits one’s adversaries.

At the height of the abuse crisis in the United States, on Nov. 30, 2002, Ratzinger answered questions at the Catholic University of San Antonio de Murcia in southeastern Spain. There are, of course, sinners in the church, he explained, “but personally I am convinced that a targeted campaign is behind the constant media reports on the sins of Catholic priests, particularly in the United States.” The goal of this campaign, he said, was to “discredit the Church.”

The American church paid dearly for its attempted cover-ups. To date, US dioceses have been forced to pay well over $2 billion (€1.5 billion) in compensation for the misdeeds of about 5,000 priests. Some dioceses have had to declare bankruptcy as a result.

The law of silence regarding abuse cases was still considered unbroken at the time. Cardinals Bernard Law of Boston and Roger Mahoney of Los Angeles were members of opposing camps within the Church, Law being conservative and Mahoney liberal. But the two men agreed that the Church’s good reputation was more important than the truth.

Part 7: Protecting Believers from Doubt